We Left Clojure. Here's 5 Things I'll Miss.

On October 11th, Appcanary relied on about 8,500 lines of clojure code. On the 12th we were down to zero. We replaced it by adding another 5,700 lines of Ruby to our codebase. Phill will be discussing why we left, and what we learned both here and at this year’s RubyConf. For now, I want to talk about what I’ll miss.

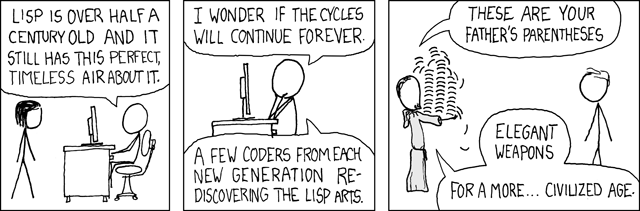

1) The joy of Lisp

There’s something magical about writing lisp. Alan Kay called it the greatest single programming language ever devised. Paul Graham called it a secret weapon. You can find tens of thousands of words on the elegant, mind-expanding powers of lisp1. I don’t think my version of the Lisp wizardry blog post would be particularly original or unique, so if you want to know more about the agony and ecstasy of wielding parenthesis, read Paul Graham.

What’s great about Clojure is that while Ruby might be an acceptable lisp, and lisp might not be an acceptable lisp, Clojure is a more than acceptable lisp. If we avoid the minefield of type systems, Clojure addresses the other 4 problems Steve Yegge discusses in the previous link2.

2) Immutability

The core data structures in clojure are immutable. If I define car to be "a dirty van",

nothing can ever change that. I can name some other thing car later, but

anything referencing that first car will always be referencing "a dirty van".

This is great for a host of reasons. For one, you get parallelization for free — since nothing will mutate your collection, mapping or reducing some function over it can be hadooped out to as many clouds as you want without changing your algorithms.

It’s also much easier to can reason about your code. There’s a famous quote by Larry Wall:

[Perl] would prefer that you stayed out of its living room because you weren’t invited, not because it has a shotgun.

He was talking about private methods, but the same is true for mutability in most languages. You call some method and who knows if it mutated a value you were using? You would prefer it not to, but you have no shotgun, and frankly it’s so easy to mutate state without even knowing that you are. Consider Python:

str1 = "My name "

str2 = str1

str1 += "is Max"

print str1

# "My name is Max"

print str2

# "My name"

list1 = [1, 2, 3]

list2 = list1

list1 += [4, 5]

print list1

# [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

print list2

# [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

Calling += on a string returned a new one, while calling += on a list

mutated it in place! I have to remember which types are mutable, and whether

+= will give me a new object or mutate the existing one depending on its type.

Who knows what might happen when you start passing your variables by reference

to somewhere else?

Not having the choice to mutate state is as liberating as getting rid of your Facebook account.

3) Data first programming

Walking away from object-oriented languages is very freeing.

I want to design a model for the game of poker. I start by listing the nouns3: “card”, “deck”, “hand”, “player”, “dealer”, etc. Then I think of the verbs, “deal”, “bet”, “fold”, etc.

Now what? Here’s a typical StackOverflow question demonstrating the confusion that comes with designing like this. Is the dealer a kind of player or a separate class? If players have hands of cards, how does the deck keep track of what cards are left?

At the end of the day, the work of programming a poker game is codifying all of

the actual rules of the game, and these will end up in a Game singleton that

does most of the work anyway.

If you start by thinking about data and the functions that operate on it, there’s a natural way to solve hard problems from the top-down, which lets you quickly iterate your design (see below). You have some data structure that represents the game state, a structure representing possible actions a player can take, and a function to transform a game state and an action into the next game state. That function encodes the actual rules of poker (defined in lots of other, smaller functions).

I find this style of programming very natural and satisfying. Of course, you can do this in any language; but I find Clojure draws me towards it, while OO languages push me away from it.

4) Unit Testing

The majority of your code is made up of pure functions. A pure function is one which always gives the same output for a given input — doesn’t that sound easy to test? Instead of setting up test harnesses databases and mocks, you just write tests for your functions.

Testing the edges of your code that talk to the outside world requires mocking, of course, and integration testing is never trivial. But the first thing you want to test is the super-complicated piece of business logic deep in your codebase. The business logic your business depends on, like for instance computing whether your version of OpenSSL is vulnerable to HeartBleed.

Clojure pushes you to make that bit of code a pure function that’s testable without setting up complicated state.

5) Refactoring

Here’s a typical clojure function

(defn foo [a b]

;; some code here

(let [c (some-function a b)]

;; a ton of

;; complicated code here

)))

In lisp-speak, a parenthesized block is called a “form”. The foo form is the outer form, and it contains the let form, which ostensibly contains other forms that do complicated things.

I know that all the complicated code inside of the let form isn’t going to

mutate any state, and that it’s only dependent on the a and b variables. This means that

refactoring this code out into its own functions is as trivial as selecting

everything between two matching parentheses and cutting and pasting it out. If

you have an editor that supports paredit-style navigation of lisp forms, you can

rearrange code at lightning speed.

-

My favourite essay of this ilk is Mark Tarver’s melancholy The Bipolar Lisp Programmer. He describes lisp as a language designed by and for brilliant failures. Back in university, I ate this shit up. My grades were obvious evidence of half the requirement of being a lisp programmer. ↩

-

I’m aware that clojure’s

gensymdoes not a hygenic macro system make. But, if you have strong opinions on hygenic macros as they relate to acceptable lisps, this article might not be for you. ↩ -

For the record, I know that this isn’t the “right” way to design OO programs, but the fact that I have to acknowledge this proves my point. ↩